Malaysia’s debate over children and smartphones has reignited follwing a recent rise of violent incidents at schools. It is a question many countries are now confronting: how young is too young for unrestricted access to smartphones and social media.

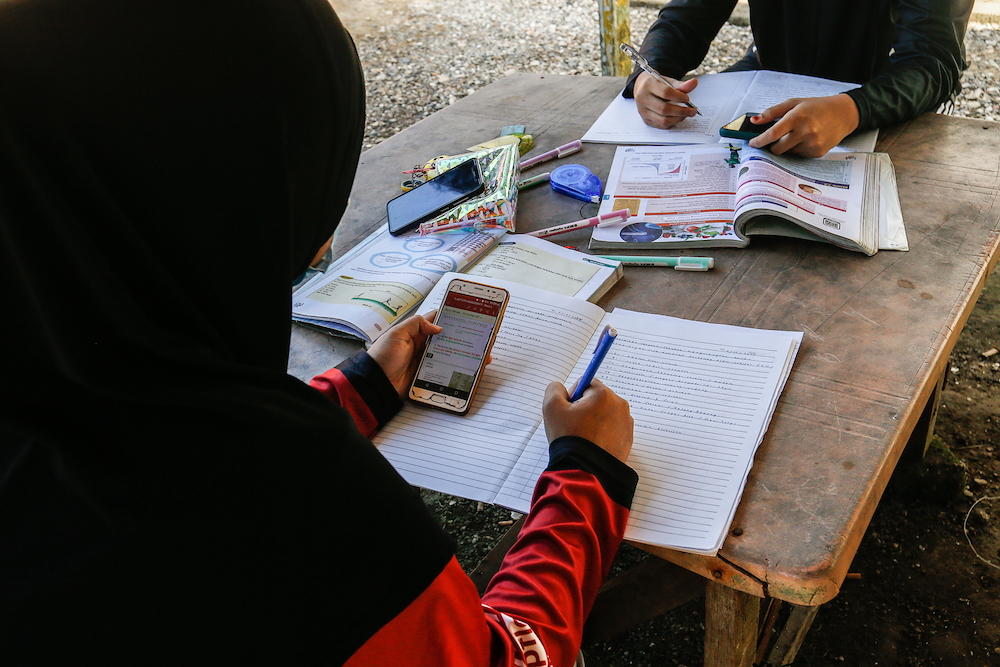

Digital access among children has become nearly universal, and the benefits are clear. Online platforms have expanded access to learning materials, social support networks, and creative outlets. But, like most things with great power, they come with great cost.

According to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) Internet Users Survey 2024, 60.7% of Malaysian children own an internet-connected device, and more than a quarter spend over five hours online daily. The same report found that one in three has encountered a form of cybercrime.

Parents are increasingly worried. The MCMC survey shows that two-thirds cite “negative influence” and more than half fear exposure to age-inappropriate or violent content, while 40% are concerned about AI-generated or deepfake material. In response, parental strictness has risen sharply, with more families setting rules and using control tools, though affordability and awareness remain uneven.

At the same time, the Malaysia’s National Health and Morbidity Survey 2023 by the Ministry of Health found that one in six children experience mental health issues, and the burden of mental health problems among children has doubled since 2019. The Malaysia Youth Mental Health Index 2023 identifies emotional health including anxiety, stress, and depression as key challenges among youths aged 15 to 30. While correlation does not equal causation, these trends have risen alongside the decade when smartphones and social media became nearly universal.

The case for restrictions

Several governments have begun imposing stricter age and usage limits. Australia’s federal government announced plans to restrict social media access for users under 16, supported by new age-verification standards. In France, smartphones are banned in primary and lower secondary schools, while the UK extended similar restrictions through its Department for Education’s mobile phone policy guidance issued earlier this year.

In Malaysia, Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil recently confirmed that the government is studying a proposal to set 16 as the minimum age to open a social media account, citing growing concerns about youth safety and exposure. The Education Ministry has said it is reviewing policies on device use in schools.

Proponents of similar policies in Malaysia argue that the issue is not technological progress but developmental readiness. Studies by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) link high levels of digital media exposure with increased risks of sleep disturbance, attention problems, and depression among children. Teachers in Malaysia have voiced similar concerns, with educators saying smartphones often disrupt lessons and that clear national guidelines are overdue.

Advocates say restricting access during school hours could help students focus, restore real-world social interaction, and protect younger users from online exploitation. Some educators also point to data from France and the UK showing improved classroom concentration and reduced bullying after school-day phone bans.

The argument against bans

Opponents argue that outright bans are neither realistic nor sustainable. Malaysia’s education system has integrated online platforms and educational apps that require mobile access. Removing smartphones entirely could hinder learning and widen the digital divide for students without alternative devices.

Critics also note that a ban does not address what happens outside of school. Without digital literacy, students remain vulnerable to misinformation, online manipulation, and addictive content.

Civil society groups have called for education rather than restriction. That means teaching children to recognise persuasive design, regulate their screen habits, and think critically about what they consume. These groups argue that responsible use, not prohibition, should be the goal.

The smartphone and mental health link

Globally, researchers continue to examine how much of the mental health crisis among adolescents is tied to smartphone use. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in his 2024 book The Anxious Generation, argues that widespread smartphone adoption between 2010 and 2020 coincided with a sharp rise in anxiety and depression among teenagers, particularly girls. He attributes this to what he calls “the Great Rewiring of Childhood,” where social validation, comparison, and entertainment moved online.

While Haidt’s conclusions are debated, follow-up studies from Oxford University (2023) and Pew Research (2024) also found consistent associations between excessive screen time, sleep deprivation, and reduced attention spans. Malaysian counsellors interviewed by Makchic and NST have reported similar behavioural changes in students, including social withdrawal and irritability when deprived of digital access.

The new complication: AI and the illusion of reality

The debate over children’s digital habits now overlaps with a larger challenge, and that is the rise of artificial intelligence. AI-generated text, images, and videos are increasingly indistinguishable from authentic content. A University of Waterloo study found that participants correctly identified AI-generated faces only 61 percent of the time. Another experiment, Seeing is Not Always Believing (Lu et al., 2023), reported that people misjudged synthetic images nearly 40 percent of the time.

For younger users, the difficulty distinguishing real from fabricated media adds another layer of risk. If adults already struggle to separate truth from simulation, it’s not a stretch to say that children face an even steeper challenge.

UNESCO urges countries to integrate AI and media literacy into national curricula, teaching students to recognise synthetic content and verify sources. Malaysia has yet to formalise such a framework.

Striking a balance

The discussion over banning smartphones or social media for under-16s often polarises into two extremes: total restriction or unrestricted access. In reality, experts say both approaches are insufficient.

According to the Malaysian Psychological Association, protecting children requires “a layered approach” that includes stronger age verification for platforms, consistent parental boundaries at home, and structured digital education in schools. The American Academy of Pediatrics offers similar guidance under its “5 Cs of Media Use” framework, encouraging parents to focus on content, context, communication, connection, and the individual child’s needs rather than raw screen-time limits.

Right now, the government is studying two separate measures: setting a minimum age of 16 for social media access and banning smartphones in schools for students under that age. Many teachers argue that phones are disruptive in classrooms, while parents worry a total ban could hinder coordination or safety.

If a social media age limit were introduced, the harder question is what counts as social media. Would platforms like WhatsApp or Telegram, which many parents and teachers rely on for daily communication, fall under the same rules as TikTok, Instagram, or X?

Enforcement would also be complex. If age verification is handled through systems such as MyDigital ID, would that extend to all messaging and content-sharing apps, or only those with public feeds and algorithmic content? Teenagers are already adept at using VPNs, alternate accounts, or secondary SIM cards. Restricting one platform could simply drive them to another that’s harder to monitor.

The debate here should be less about access and more about balance. It is not whether young people should use smartphones or social media, but how and when, and whether adults are prepared to model that balance themselves.

A collective responsibility

The question of whether Malaysia should ban smartphones or social media for minors does not have a simple answer. Regulation can set guardrails, but ultimately, the health of Malaysia’s next generation will depend on balance between freedom and protection, exposure and understanding, innovation and responsibility.

As artificial intelligence reshapes how information, identity, and influence are produced, digital literacy is becoming as essential as reading and writing. A smartphone ban might delay exposure, but education is what determines resilience.

Malaysia’s challenge is not whether to connect its children, but how to ensure that connection builds understanding instead of confusion. The technology itself isn’t going away. The question is whether we can grow wise enough to use it well.

0 comments :

Post a Comment